The U.S. ag sector lacks a universal definition for a recession, but experts rely on several key indicators to evaluate economic downturns. These include economic metrics, financial conditions, and industry sentiment.

There is no single, universally accepted definition for a recession in the U.S. agricultural sector. However, several key indicators and factors are commonly used to assess whether the agricultural economy is experiencing a downturn or recession. Here’s how experts determine if there’s a recession in the U.S. ag sector:

Economic indicators

• Declining Farm Income: A significant and prolonged decrease in net farm income is a primary indicator of an agricultural recession.

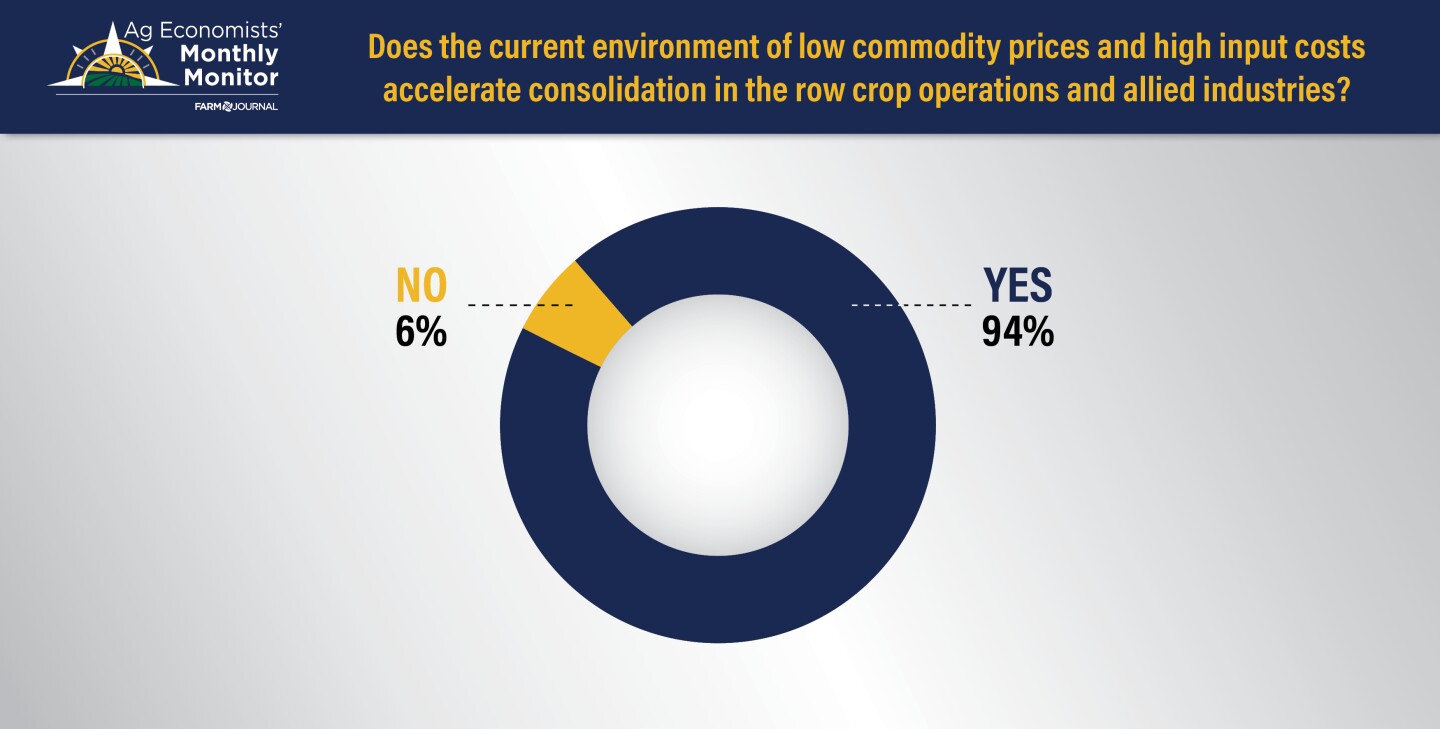

• Commodity prices: Sharp declines in prices for major agricultural commodities, such as corn and soybeans, can signal economic distress.

Input costs: Elevated prices for farm inputs like fertilizers, seeds, and fuel, especially when combined with lower commodity prices, can squeeze profit margins.

Agricultural exports: A reduction in agricultural exports can indicate weakening demand and contribute to economic stress.

Financial metrics

• Debt-to-asset ratios: Increasing debt levels relative to assets may suggest financial strain on farms.

• Credit conditions: Weakening credit conditions, such as tightening lending standards or increased loan delinquencies, can indicate economic troubles.

• Farmland values: Falling farmland values often accompany agricultural recessions.

Sentiment and surveys

• Farmer sentiment indices: Measures like Purdue’s Farmer Sentiment Index can provide insights into the sector’s economic health. For example, the index hit an 8-year low in August 2024, indicating pessimism among farmers.

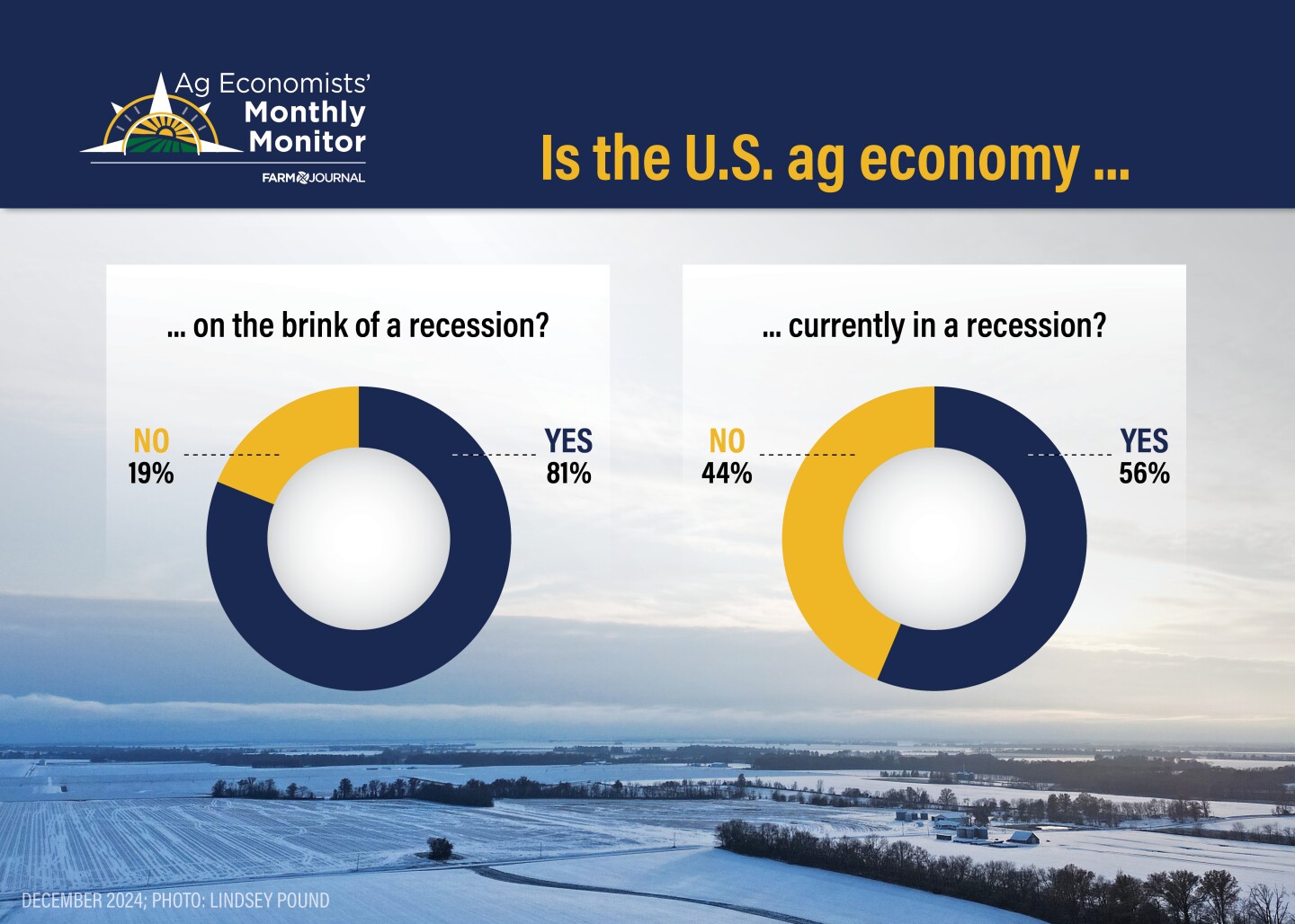

• Economist surveys: Polls of agricultural economists can offer expert assessments of the sector’s condition. In a recent survey, more than half of the economists believed the U.S. agricultural economy was in a recession.

Defining an agricultural recession. While there’s no official definition, some economists propose their own criteria:

• Michael Langemeier of Purdue University defines an agricultural recession as “one of the worst years we’ve seen in the last 20.”

• The National Bureau of Economic Research’s general recession definition, which involves “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months,” can be adapted to the agricultural context.

• Some economists consider the sector to be in recession when there’s widespread financial stress, reduced farm income, and pessimism across multiple agricultural subsectors.

Of note: The agricultural economy can be in recession even if the broader U.S. economy is not, due to sector-specific factors like weather, trade policies, and global market conditions. Additionally, different segments of agriculture (e.g., crops vs. livestock) may experience varying economic conditions simultaneously as is currently the case with crop incomes down and most livestock and dairy incomes up.

Bottom line: At least two of the financial metrics are not being met — farmland values have not declined (in some states and regions they have) and the 2024 debt-to-equity and debt-to-asset ratios declined versus 2023. And, ag industry sentiment has improved with the prospect of the Trump administration since they want fewer regs for the ag industry.

Finally, Willard Cochrane, a prominent agricultural economist, developed the concept of the “agricultural treadmill” to explain the challenges faced by farmers in maintaining profitability. Cochrane was the lead economist at USDA in the 1960s (for USDA Secretary Orville Freeman) and a professor at the Univ. of Minnesota. According to Cochrane’s agricultural treadmill theory:

• Early adopters of new technology initially benefit from increased productivity and lower production costs.

• As more farmers adopt the technology, overall production increases, leading to lower prices for agricultural products.

• The initial advantage gained by early adopters disappears as prices fall, eroding profits.

• This cycle repeats continuously, forcing farmers to constantly adopt new technologies to remain competitive.

• Farmers who cannot keep up with technological advancements often struggle financially and may be forced out of business.

• More successful farmers expand their operations, often acquiring land from those who exit farming.

Cochrane argued that this process leads to:

• Constant pressure on farmers to increase productivity and efficiency.

• A reduction in the number of farms and farmers over time.

• Difficulty for farmers to maintain sustainable incomes solely through farming.

He concluded that despite enormous increases in productivity, farming generally remains unprofitable for many. Cochrane also observed that government payments, while providing short-term benefits, could ultimately work against farmers by becoming capitalized into land values and increasing production costs.

In essence, Cochrane’s theory emphasizes the ongoing struggle farmers face to remain profitable in an environment of technological change and market pressures. Because of the years when U.S. ag exports and the ag trade surplus were rising, because of the first NAFTA and China joining the WTO, some thought we had broken out of the treadmill. Then, ethanol demand made some think the principles of agricultural economics had been suspended. Alas, both were errant assumptions.